Overview

In general, rate limiting is used to control the consumption rate of a resource. For example, up to 10 requests can be served by the server per minute. Or up to 1MB data can be sent to the network per second. Rate limiting is necessary for protecting a system from being overloaded.

Algorithms

There are many rate limiting algorithms. I will only list a few of them. And we

assume the use case is to limit the rate of requests to a server. The code in

this article can be found at

Github. For all

implementations below, we assume there is a RateLimiter class and a driver

class defined as follows:

RateLimiter class:

public abstract class RateLimiter {

protected final int maxRequestPerSec;

protected RateLimiter(int maxRequestPerSec) {

this.maxRequestPerSec = maxRequestPerSec;

}

abstract boolean allow();

}

Driver class:

import java.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

final int MAX_REQUESTS_PER_SEC = 10;

RateLimiter rateLimiter = ; // new a RateLimiter here

Thread requestThread = new Thread(() -> {

sendRequest(rateLimiter, 10, 1);

sendRequest(rateLimiter, 20, 2);

sendRequest(rateLimiter,50, 5);

sendRequest(rateLimiter,100, 10);

sendRequest(rateLimiter,200, 20);

sendRequest(rateLimiter,250, 25);

sendRequest(rateLimiter,500, 50);

sendRequest(rateLimiter,1000, 100);

});

requestThread.start();

requestThread.join();

}

private static void sendRequest(RateLimiter rateLimiter, int totalCnt, int requestPerSec) {

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

CountDownLatch doneSignal = new CountDownLatch(totalCnt);

for (int i = 0; i < totalCnt; i++) {

try {

new Thread(() -> {

while (!rateLimiter.allow()) {

try {

TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS.sleep(10);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

doneSignal.countDown();

}).start();

TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS.sleep(1000 / requestPerSec);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

try {

doneSignal.await();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

double duration = (System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime) / 1000.0;

System.out.println(totalCnt + " requests processed in " + duration + " seconds. "

+ "Rate: " + (double) totalCnt / duration + " per second");

}

}

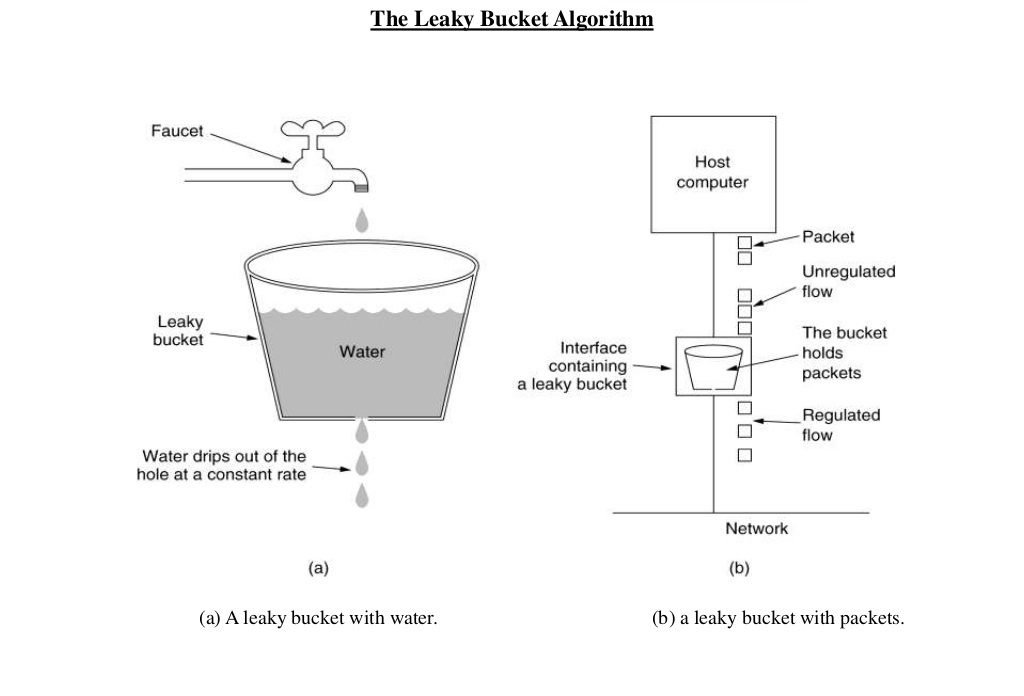

Leaky Bucket

The following image perfectly illustrates the leaky bucket algorithm.

(Image credit: [1])

(Image credit: [1])

The image shows the usage of leaky bucket algorithm in traffic shaping. If we map it our limiting requests to server use case, water drops from the faucets are the requests, the bucket is the request queue and the water drops leaked from the bucket are the responses. Just as the water dropping to a full bucket will overflow, the requests arrive after the queue becomes full will be rejected.

As we can see, in the leaky bucket algorithm, the requests are processed at an approximately constant rate, which smooths out bursts of requests. Even though the incoming requests can be bursty, the outgoing responses are always at a same rate.

A simple implementation for demonstration purpose:

public class LeakyBucket extends RateLimiter {

private long nextAllowedTime;

private final long REQUEST_INTERVAL_MILLIS;

protected LeakyBucket(int maxRequestPerSec) {

super(maxRequestPerSec);

REQUEST_INTERVAL_MILLIS = 1000 / maxRequestPerSec;

nextAllowedTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

}

@Override

boolean allow() {

long curTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

synchronized (this) {

if (curTime >= nextAllowedTime) {

nextAllowedTime = curTime + REQUEST_INTERVAL_MILLIS;

return true;

}

return false;

}

}

}

Token Bucket

Suppose there are a few tokens in a bucket. When a request comes, a token has to be taken from the bucket for it to be processed. If there is no token available in the bucket, the request will be rejected and the requester has to retry later. The token bucket is also refilled per time unit.

In this way, we can limit the requests per user per time unit by assigning a bucket with fixed amount of tokens to each user. When a user uses up all the tokens in a time period, we know that he has exceeded the limit and reject his requests until his bucket is refilled.

As we can see, in the token bucket algorithm, the request processing rate is not capped, which means it only guarantees an average processing rate will not exceeds the maximum rate. But in some period, the real-time processing rate can be higher than maximum.

A simple implementation for demonstration purpose:

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class TokenBucket extends RateLimiter {

private int tokens;

public TokenBucket(int maxRequestsPerSec) {

super(maxRequestsPerSec);

this.tokens = maxRequestsPerSec;

new Thread(() -> {

while (true) {

try {

TimeUnit.SECONDS.sleep(1);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

refillTokens(maxRequestsPerSec);

}

}).start();

}

@Override

public boolean allow() {

synchronized (this) {

if (tokens == 0) {

return false;

}

tokens--;

return true;

}

}

private void refillTokens(int cnt) {

synchronized (this) {

tokens = Math.min(tokens + cnt, maxRequestPerSec);

notifyAll();

}

}

}

In this program, we have two threads. One keeps requesting tokens from the bucket and one keeps refilling the bucket. In the first phase, the request rate is 1 per second. In the second phase, the request rate is 2 per second. So on and so forth. If we run the driver class we can get the following result:

10 requests processed in 10.043 seconds. Rate: 0.9957184108334164 per second

20 requests processed in 10.073 seconds. Rate: 1.9855058076044871 per second

50 requests processed in 10.177 seconds. Rate: 4.913039206052865 per second

100 requests processed in 10.357 seconds. Rate: 9.655305590421937 per second

200 requests processed in 19.536 seconds. Rate: 10.237510237510238 per second

250 requests processed in 25.074 seconds. Rate: 9.97048735742203 per second

500 requests processed in 50.203 seconds. Rate: 9.959564169471943 per second

1000 requests processed in 100.36 seconds. Rate: 9.964129135113591 per second

From the result, we see that in the first phase, the process rate is 1 per second, same as the request rate because it has not reached the max limit (10 tokens / second) yet. Same for the second and the third phase when the request rate is 2 and 5 per second respectively. Then from the fourth phase, the request rate has exceeded the limit. But with the token bucket rate limiting mechanism, the average processing rate can be controlled at around 10 per second.

There is an improvement of above code - instead of using a dedicated thread to

refill the bucket with fixed amount tokens, we can refill it lazily when a

request comes. The amount of tokens to refill equals to (current time - last

refill time) * max allowed tokens per time unit. The improved implementation:

public class TokenBucketLazyRefill extends RateLimiter {

private int tokens;

private long lastRefillTime;

public TokenBucketLazyRefill(int maxRequestPerSec) {

super(maxRequestPerSec);

this.tokens = maxRequestPerSec;

this.lastRefillTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

}

@Override

public boolean allow() {

synchronized (this) {

refillTokens();

if (tokens == 0) {

return false;

}

tokens--;

return true;

}

}

private void refillTokens() {

long curTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

double secSinceLastRefill = (curTime - lastRefillTime) / 1000.0;

int cnt = (int) (secSinceLastRefill * maxRequestPerSec);

if (cnt > 0) {

tokens = Math.min(tokens + cnt, maxRequestPerSec);

lastRefillTime = curTime;

}

}

}

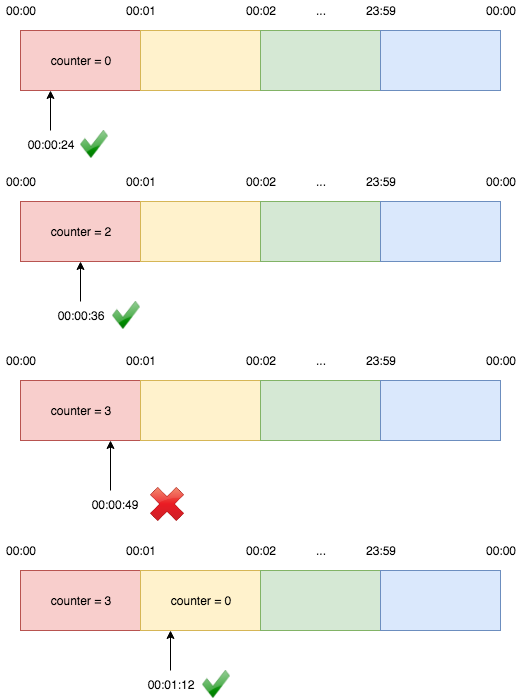

Fixed Window Counter

Fixed window counter algorithm divides the timeline into fixed-size windows and

assign a counter to each window. Each request, based on its arriving time, is

mapped to a window. If the counter in the window has reached the limit, requests

falling in this window should be rejected. For example, if we set the window

size to 1 minute. Then the windows are [00:00, 00:01), [00:01, 00:02),

...[23:59, 00:00). Suppose the limit is 2 requests per minute:

A request comes at 00:00:24 belongs to window 1 and it increases the window’s counter to 1. The next request comes at 00:00:36 also belongs to window 1 and the window’s counter becomes 2. The next request that comes at 00:00:49 is rejected because the counter has exceeded the limit. Then the request comes at 00:01:12 can be served because it belongs to window 2.

A simple implementation for demonstration purpose:

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap;

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentMap;

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger;

public class FixedWindowCounter extends RateLimiter {

// TODO: Clean up stale entries

private final ConcurrentMap<Long, AtomicInteger> windows = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

protected FixedWindowCounter(int maxRequestPerSec) {

super(maxRequestPerSec);

}

@Override

boolean allow() {

long windowKey = System.currentTimeMillis() / 1000 * 1000;

windows.putIfAbsent(windowKey, new AtomicInteger(0));

return windows.get(windowKey).incrementAndGet() <= maxRequestPerSec;

}

}

Cleaning up of stale entries is omitted in above code. We can run a job to clean stale windows regularly. For instance, schedule a task running at 00:00:00 to remove all the entries created in previous day.

From the implementation perspective, one advantage of this approach is, unlike token bucket where we have to lock the bucket while getting tokens from it, we can use an atomic operation to increase the counter in each window to make the code lock-free.

Obviously, fixed window counter algorithm only guarantees the average rate

within each window but not across windows. For example, if the expected rate is

2 per minute and there are 2 requests at 00:00:58 and 00:00:59 as well as 2

requests at 00:01:01 and 00:01:02. Then the rate of both window [00:00, 00:01)

and window [00:01, 00:02) is 2 per minute. But the rate of window [00:00:30,

00:01:30) is in fact 4 per minute.

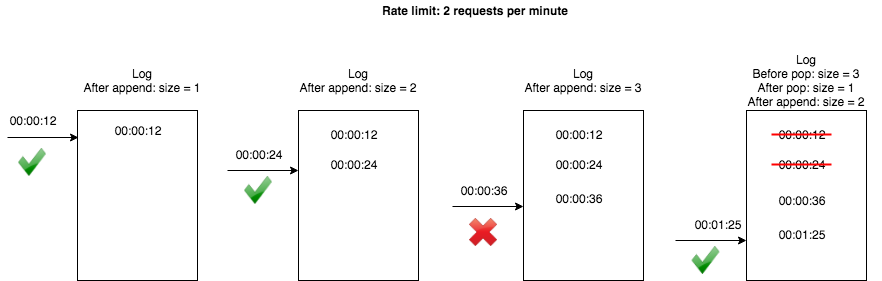

Sliding Window Log

Sliding window log algorithm keeps a log of request timestamps for each user. When a request comes, we first pop all outdated timestamps before appending the new request time to the log. Then we decide whether this request should be processed depending on whether the log size has exceeded the limit. For example, suppose the rate limit is 2 requests per minute:

A simple implementation for demonstration purpose:

import java.util.LinkedList;

import java.util.Queue;

public class SlidingWindowLog extends RateLimiter {

private final Queue<Long> log = new LinkedList<>();

protected SlidingWindowLog(int maxRequestPerSec) {

super(maxRequestPerSec);

}

@Override

boolean allow() {

long curTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

long boundary = curTime - 1000;

synchronized (log) {

while (!log.isEmpty() && log.element() <= boundary) {

log.poll();

}

log.add(curTime);

return log.size() <= maxRequestPerSec;

}

}

}

Though in above implementation we use a lock while performing operations on the

log, in practice, Redis’s sorted set and ZREMRANGEBYSCORE command can provide

atomic operations to accomplish this [4].

Note: If we run our unmodified driver class using this rate limiter, it will never end. Think why?

The advantage of sliding window log over fixed window counter is that, instead

of ensuring an average rate within each window, it provides a more accurate rate

limit because the window boundary is dynamic instead of fixed. For example, if

the time unit is 1 minute, fixed window counter guarantees an average rate in

window [00:00, 00:01), [00:01,00:02), etc. But sliding window log guarantees

that for each request arrives at time t, the rate in window (t - 1, t] won’t

exceed limit.

The disadvantage of this approach is its memory footprint. We notice that, even if a request is rejected, its request time is recorded in the log, making the log unbounded.

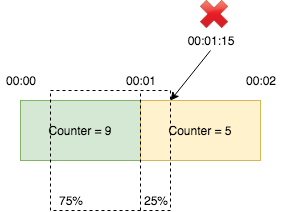

Sliding Window

Sliding window counter is similar to fixed window counter but it smooths out

bursts of traffic by adding a weighted count in previous window to the count in

current window. For example, suppose the limit is 10 per minute. There are 9

requests in window [00:00, 00:01) and 5 reqeuests in window [00:01, 00:02).

For a requst arrives at 00:01:15, which is at 25% position of window

[00:01, 00:02), we calculate the request count by the formula:

9 x (1 - 25%) + 5 = 11.75 > 10. Thus we reject this request. Even though both

windows don’t exceed the limit, the request is rejected because the weighted sum

of previous and current window does exceed the limit.

This is still not accurate becasue it assumes that the distribution of requests in previous window is even, which may not be true. But compares to fixed window counter, which only guarantees rate within each window, and sliding window log, which has huge memory footprint, sliding window is more practical.

A simple implementation for demonstration purpose:

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap;

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentMap;

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger;

public class SlidingWindow extends RateLimiter {

// TODO: Clean up stale entries

private final ConcurrentMap<Long, AtomicInteger> windows = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

protected SlidingWindow(int maxRequestPerSec) {

super(maxRequestPerSec);

}

@Override

boolean allow() {

long curTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

long curWindowKey = curTime / 1000 * 1000;

windows.putIfAbsent(curWindowKey, new AtomicInteger(0));

long preWindowKey = curWindowKey - 1000;

AtomicInteger preCount = windows.get(preWindowKey);

if (preCount == null) {

return windows.get(curWindowKey).incrementAndGet() <= maxRequestPerSec;

}

double preWeight = 1 - (curTime - curWindowKey) / 1000.0;

long count = (long) (preCount.get() * preWeight

+ windows.get(curWindowKey).incrementAndGet());

return count <= maxRequestPerSec;

}

}

Conclusion

In this article we have learned several rate limiting algorithms and their simple implementations. In next post, we will analyze how rate limiting is implemented in Google guava library.

Reference

[1] Leaky Bucket & Tocken Bucket - Traffic shaping

[2] How to Design a Scalable Rate Limiting Algorithm

[3] An alternative approach to rate limiting

[4] Better Rate Limiting With Redis Sorted Sets